The Revolutions of 1848

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Camillo-Benso-conte-di-Cavour

https://www.britannica.com/place/Piedmont-region-Italy

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Giuseppe-Mazzini

http://www.historydiscussion.net/history/history-of-italy/role-of-garibaldi-in-the-formation-of-italy/1883

http://dbpedia.org/page/Capture_of_Rome

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prisoner_in_the_Vatican

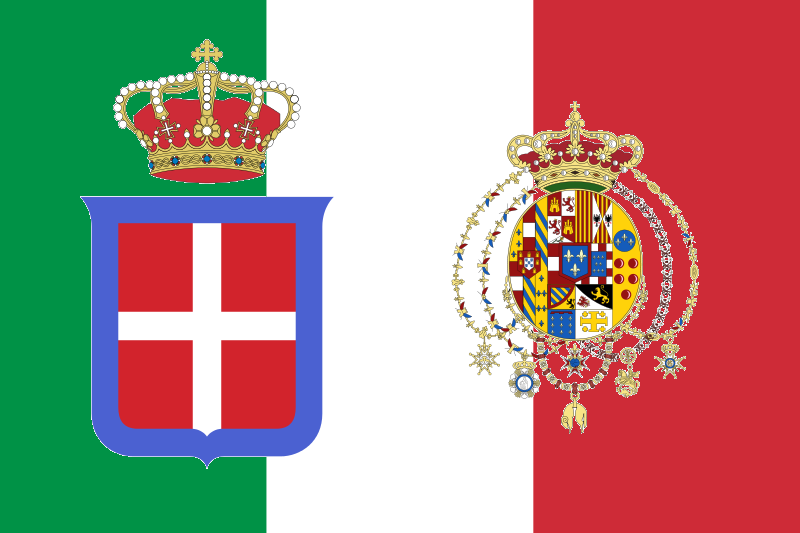

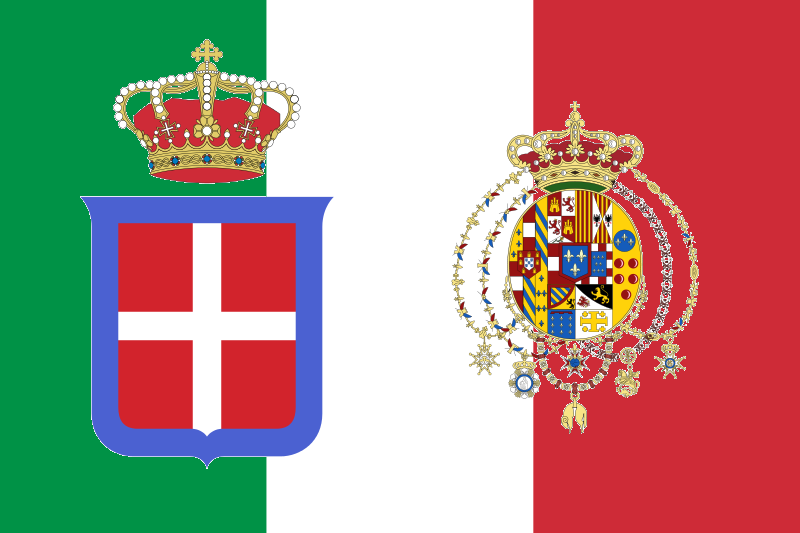

House of Savoy, Italian Savoia, French Savoie, historic dynasty of Europe

Camillo Benso, count di Cavour

Piedmontese statesman, a conservative whose exploitation of international rivalries and of revolutionary movements brought about the unification of Italy (1861) under the House of Savoy, with himself as the first prime minister of the new kingdom.

(born August 10, 1810, Turin, Piedmont, French Empire—died June 6, 1861, Turin, Italy),

The Cavours were an ancient family that had served the House of Savoy as soldiers and officials since the 16th century. Genevan by birth and Calvinist by religion, his mother brought into the Cavour family the influence of Geneva, a city open to all the political, religious, and social movements of the period.

The French Revolution imperilled the fortunes of the Cavours because of their close ties with the ancien régime; but Cavour’s father, Michele, reestablished the family in an eminent position in Napoleonic society. Camillo even had as godparents Prince Camillo Borghese—after whom he was named—and Pauline Bonaparte, the Prince’s wife and Napoleon’s favourite sister.

Michele Giuseppe Francesco Antonio Benso de Cavour

aka Michele Antoine Bens de Cavour or Michele Benso de Cavour

Piedmontese Noble (November 30, 1781 in Turin - June 15, 1850 in Turin),5th Marquis of Cavour, Baron Bens of Cavour and of the Empire,

[father of Camillo above] Michele Benso de Cavour is the son of Giuseppe Filippo Benso2 (1741-1807), 4th Marquis of Cavour, count of Isolabella and Cellarengo, lord of Santena, and of Philippine de Sales (Turin, June 15, 1762-Turin, April 5 1849) lady of honor (1st lady) of Pauline Bonaparte princess Borghese (1810), countess of the Empire.

After the Napoleonic invasion of Piedmont in 1796, the Cavours spent very hard years and certain members of the family were forced to leave the country or to withdraw until better times. Michele Benso is robbed of the title of Marquis. In 1799, while the Austro-Russian offensive momentarily chased the French from Italy, the Cavours reaffirm their loyalty to the House of Savoy

In 1801, Michele Benso met his future wife, Adélaïde Suzanne de Sellon (1780-1846), in Geneva, where he was to escape anti-aristocratic persecution. Michele and Adèle get married on April 17, 1805. Adèle de Sellon belongs to a Calvinist family of French origin from Geneva. From their marriage, their eldest son Gustavo was born in Turin on June 27, 18064. In 1807, on the death of his father Filippo, Michele Benso received his inheritance

In 1809, Michele Benso Cavour was appointed baron of the Empire and he became chamberlain and one of the trusted men of Prince Camille Borghèse, governor of the French departments in Italy and who has his court in Turin.

Camillo was born in Turin.'On August 10, 1810, when the Cavour family was at its peak,

[named after Prince Camillo Borghese, his godfather, married to Princess Pauline Bonaparte.]

After the post-Napoleonic restoration of 1814, Michele Cavour regains his title of marquis and manages with great political skill the Cavour in the difficult period of the transitional regime.

The family gradually became a defender of rationalist and Masonic values to Jesuit Catholicism which characterized the kingdom of Sardinia after 1815. They became close to Charles-Albert of Sardinia future King Michele Cavour was appointed mayor of Turin in 1833 and chief of police in 1837-47

Carbonari

(kärbōnä`rē) [Ital.,=charcoal burners], members of a secret society that flourished in Italy, Spain, and France early in the 19th cent. Possibly derived from Freemasonry, the society originated in the kingdom of Naples in the reign of Murat (1808–15) and drew its members from all stations of life, particularly from the army. It was closely organized, with a ritual, a symbolic language, and a hierarchy.

Beyond advocacy of political freedom its aims were vague. The Carbonari were partially responsible for uprisings in Spain (1820), Naples (1820), and Piedmont (1821). After 1830 the Italian Carbonari gradually were absorbed by the Risorgimento movement; elsewhere they disappeared.

Risorgimento

(rēsôr'jēmĕn`tō) [Ital.,=resurgence], in 19th-century Italian history, period of cultural nationalism and of political activism, leading to unification of Italy.Roots of the Risorgimento

The Risorgimento's roots lie in 18th-century Italian culture in the works of such people as Ludovico Antonio Muratori, Vittorio Alfieri, and Antonio Genovesi. Italy had not been a single political unit since the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th cent., and from the 16th through the 18th cent. foreign domination or influence was virtually complete. During the French Revolutionary Wars and the period dominated by Napoleon I, the temporary expulsion of Austrian and other repressive regimes and the formation of new states in Italy (see Cisalpine Republic) encouraged hopes for unification.

Early Years and Factions

Secret societies such as the Carbonari appeared and carried on revolutionary activity after the restoration of the old order by the Congress of Vienna (1814–15). The Carbonari engineered uprisings in the Two Sicilies (1820) and in the kingdom of Sardinia (1821). Despite severe reprisals inspired by the Holy Alliance, new uprisings occurred in 1831 in the Papal States, Modena, and Parma. Italian literature of this period, especially the novels of Alessandro Manzoni and the marchese d'Azeglio and the poetry of Ugo Foscolo and Giacomo Leopardi, did much to stimulate Italian nationalism.

The Risorgimento was primarily a movement of the middle class and the nobility; since economic issues were virtually ignored, the peasantry remained indifferent to its ideals. Political activity was carried on by three groups. Giuseppe Mazzini led the radical faction through his secret society Giovine Italia [young Italy], founded in 1831. Its program was republican and anticlerical; it vaguely alluded to social and economic reforms. The conservative and clerical elements among the nationalists generally advocated a federation of Italian states under the presidency of the pope. The moderates—the propertied bourgeoisie and the north Italian promoters of industry—favored unification of Italy under a king of the house of Savoy. This monarch, as it later turned out, was Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia.

Giuseppe Mazzini,

Genoese propagandist and revolutionary,founder of the secret revolutionary society Young Italy (1832), and a champion of the movement for Italian unity known as the Risorgimento. An uncompromising republican, he refused to participate in the parliamentary government that was established under the monarchy of the House of Savoy when Italy became unified and independent

His love of freedom led him to join the Carbonari, a secret society pledged to overthrow absolute rule in Italy. In 1830 he was betrayed to the police, arrested, and interned at Savona,

When released early in 1831, he was ordered either to leave Piedmont or to live in some small town.

His first public gesture was an “open letter” to Charles Albert, the king of Piedmont, urging him to give Piedmont constitutional government, to lead a national movement, and to expel the Austrians from Lombardy-Venetia and their other Italian strongholds.

The letter was circulated in Italy, but Charles Albert’s only reaction was to threaten Mazzini with arrest if he returned to Piedmont.

A projected rising in Piedmont in 1833 was discovered before it had begun;

12 conspirators were executed, one committed suicide, and Mazzini was tried in absence and condemned to death.A few months later, when he had moved to Switzerland to escape from the French police, he tried to rally 1,000 volunteers to invade Savoy

(then part of the kingdom of Piedmont).

Only 200 could be mustered, and the force was disbanded.

https://www.britannica.com/place/Piedmont-region-Italy

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Giuseppe-Mazzini

The main impetus to the Risorgimento came from reforms introduced by the French when they dominated Italy during the period of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars (1796–1815). A number of Italian states were briefly consolidated, first as republics and then as satellite states of the French empire, and, even more importantly, the Italian middle class grew in numbers and was allowed to participate in government.

After Napoleon’s defeat in 1815, the Italian states were restored to their former rulers. Under the domination of Austria, these states took on a conservative character. Secret societies such as the Carbonari opposed this development in the 1820s and ’30s. The first avowedly republican and national group was Young Italy, founded by Giuseppe Mazzini in 1831. This society, which represented the democratic aspect of the Risorgimento, hoped to educate the Italian people to a sense of their nationhood and to encourage the masses to rise against the existing reactionary regimes. Other groups, such as the Neo-Guelfs, envisioned an Italian confederation headed by the pope; still others favoured unification under the house of Savoy, monarchs of the liberal northern Italian state of Piedmont-Sardinia.#

The Revolutions of 1848

The first of the Revolutions of 1848 erupted in Palermo on January 9. Starting as a popular insurrection, it soon took on overtones of Sicilian separatism and spread throughout the island. Piecemeal reforms proved inadequate to satisfy the revolutionaries, both noble and bourgeois, who were determined to have a new and more liberal constitution. Ferdinand II of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies was the first to grant one (January 29, 1848). Other rulers were compelled to follow his example: Leopold II on February 17, Charles Albert on March 4, and Pope Pius IX on March 14

After the failure of liberal and republican revolutions in 1848, leadership passed to Piedmont.

Throughout Europe the forces of reaction were triumphant. The Revolutions of 1848 were suppressed in Vienna, Prague, Budapest, and Paris. In Naples the king regained power in a coup on May 15 and went on to reconquer Sicily. Meanwhile, in Rome the papacy reintroduced a range of obscurantist policies.

Piedmont- Austria War .Franco-Austrian War, Austro-Sardinian War or Italian War of 1859,

was fought by the French Empire and the Kingdom of Sardinia against the Austrian Empire in 1859

Cavour felt that the help of France was necessary’ to declare war against Austria.

So he asked Emperor Napoleon III of France for help.

As Napoleon III was an active member of the ‘Carbonary Committee’ he assured to help Cavour.

Venice, however, under the dictatorship of Daniele Manin, refused to accept the Salasco armistice and resisted the Austrian siege. Leopold II of Tuscany took refuge in the Bourbon fortress of Gaeta in February 1849, when the democrats Giuseppe Montanelli and Francesco Domenico Guerrazzi were on the verge of taking control of the government and proclaiming an Italian constituent assembly.

In Rome the minister Pellegrino Rossi, a former member of the Carbonari who had promoted conciliatory policies after returning from exile in France, was assassinated on November 15, 1848. This event triggered a democratic insurgency and caused Pius IX to flee to the safety of Gaeta. A constituent assembly elected by universal male suffrage proclaimed the Roman Republic on February 5, 1849 With French help, the Piedmontese defeated the Austrians in 1859

Unification of Central Italy:

The second step towards the unification of Italy was the unification of Central states like Parma, Modena and Tuscany with Piedmont. Lord Palmerston, the Prime Minister of England refused to interfere in the internal affair of any country. As the Prime Minister of Piedmont, Cavour again tried to appease Napoleon III. He promised to give Nice and Savoy to Napoleon ill if he would remain neutral.

The people of these states voted unanimously in favour of annexation. Parma, Modena, Tuscany and Romagna, one of the Papal States agreed to side with Piedmont. Savoy and Nice were given to Napoleon III. In this way, four states were united with Italy in the second step.

Annexation of Naples and Sicily:

At that time, in South Italy, the people of Naples and Sicily were revolted against the Bourbon dynasty. The rebels requested Garibaldi to lead the revolt. He was honoured by the people of Naples and Sicily. Under leadership of Garibaldi, the rebels occupied Sicily. Then he went to Naples and captured it. Naples and Sicily were annexed with Piedmont along with some portions of Rome. It was the ‘third step’ towards the unification of Italy.

Campaign of Rome:

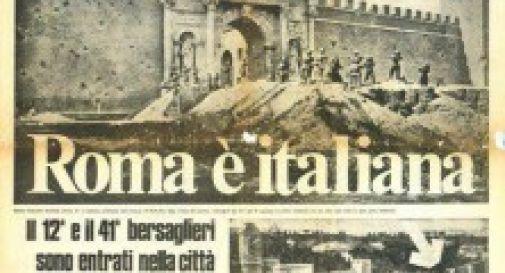

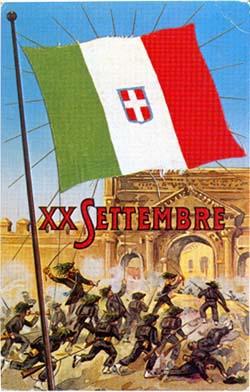

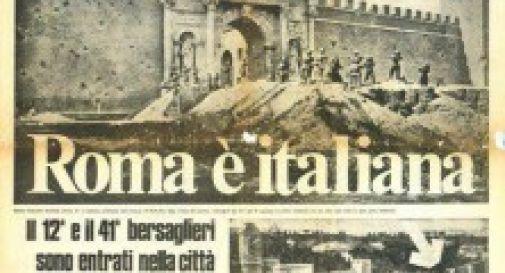

The capture of Rome (Italian: Presa di Roma)

On 11 September, 1960, he attacked the Papal States. The Papal army was defeated in Castelfidaro and Anacona. Then Victor Emanuel occupied ‘Umvia’ and ‘Marches’ and annexed them with Piedmont-Sardinia.

During this time, Garibaldi returned with the occupation of Sicily and Naples and surrendered his conquest to Victor Emanuel and retired to the island of Caprera. It was the ‘fourth step’ towards the unification of Italy.

The First Parliament of Italy:

The whole of Italy had been united except Venetia and Rome under the leadership of Piedmont-Sardinia. The representatives of all the states met on 18 February, 1861 and the First Parliament of Italy was established. “By the mercy of God and Will of Nation.” Victor Emanuel was declared as the King of Italy. By the inspiration of Mazzini, the bravery of Garibaldi and the leadership of Cavour, Italy was established as a nation State.

Annexation of Venetia:

The Austro-Prussian War of 1866 was a good news for Italy. In this war Italy supported Prussia against Austria. Austria was defeated in this Austro-Prussian battle or the battle of Sadwa. The ‘Treaty of Prague’ was concluded between Austria and Prussia in 1866. According to it, Austria ceded Venetia to Italy. The annexation of Venetia to Italy was the ‘fifth step’ towards the formation of the nation state of Italy.

Basilica San Marco din Venetia

Annexation of Rome:

In 1870 the battle of Sedan was fought between France and Prussia King Victor Emanuel II of Piedmont-Sardinia took the advantage of this opportunity. France withdrew its army from Rome at this time Emanuel attacked Rome and captured it.

Really, Unification of Italy was a cardinal epoch in the history of the world. In the formation of this nation state, Mazzini rose as the saint. Garibaldi stood as the sword and Cavour was regarded as the brain. The active measures taken by Victor Emanuel II also helped in the unification of Italy. In due course of time Italy was able to play her role in the International field.

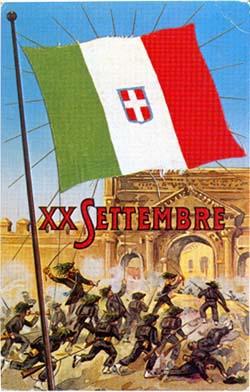

20 September 1870 was the final event of the long process of Italian unification known as the Risorgimento, marking both the final defeat of the Papal States under Pope Pius IX and the unification of the Italian peninsula under King Victor Emmanuel II of the House of Savoy.

The capture of Rome ended the approximate 1,116 year reign (754 to 1870 AD) of the Papal States under the Holy See and is today widely memorialized throughout Italy with the Via XX Settembre street name in virtually every town of any size

On October 2, 1870 Rome was annexed with Italy. It was the last step towards the Unification of Italy. The whole of Italy was bound in the rope of nationalism.

http://www.historydiscussion.net/history/history-of-italy/role-of-garibaldi-in-the-formation-of-italy/1883

http://dbpedia.org/page/Capture_of_Rome

The Italian army, commanded by General Raffaele Cadorna, crossed the papal frontier on 11 September and advanced toward Rome, moving slowly in the hope that a peaceful entry could be negotiated.

The Papal garrisons had retreated from Orvieto, Viterbo, Alatri, Frosinone and other strongholds in Lazio, Pius IX himself being convinced of the inevitability of a surrender

When the Italian Army approached the Aurelian Walls that defended the city, the papal force was commanded by General Hermann Kanzler, and was composed of the Swiss Guards and a few "zouaves"—volunteers from France, Austria, the Netherlands, Spain, and other countries—for a total of 13,157 men against some 50,000 Italians

The Italian army reached the Aurelian Walls on 19 September and placed Rome under a state of siege. Pius IX decided that the surrender of the city would be granted only after his troops had put up enough resistance to make it plain that the take-over was not freely accepted. On 20 September, after a cannonade of three hours had breached the Aurelian Walls at Porta Pia (Breccia di Porta Pia), the crack Piedmontese infantry corps of Bersaglieri entered Rome. In the event 49 Italian soldiers and 19 Papal Zouaves died. Rome and the region of Lazio were annexed to the Kingdom of Italy after a plebiscite on 2 October.

The Leonine City, excluding the Vatican, seat of the Pope, was occupied by Italian soldiers on 21 September. The Italian government had intended to let the Pope keep the Leonine City, but the Pope would not agree to give up his claims to a broader territory and claimed that since his army had been disbanded, apart from a few guards, he was unable to ensure public order even in such a small territory

A prisoner in the Vatican or prisoner of the Vatican

The Papal States were able to fend off efforts to conquer them largely through the pope's influence over the leaders of stronger European powers such as France and Austria. When Rome was eventually taken, the Italian government reportedly intended to let the pope keep the part of Rome west of the Tiber called the Leonine City as a small remaining Papal State, but Pius IX refused.[3] One week after entering Rome, the Italian troops had taken the entire city save for the Apostolic Palace; the inhabitants of the city then voted to join Italy

For the next 59 years, the popes refused to leave the Vatican in order to avoid any appearance of accepting the authority wielded by the Italian government over Rome as a whole. During this period, popes also refused to appear at Saint Peter's Square or at the balcony of the Vatican Basilica facing it, as the square in front of the basilica was occupied by Italian troops. During this period, popes granted the Urbi et Orbi blessings from a balcony facing a courtyard, or from inside the basilica, and papal coronations were instead held at the Sistine Chapel. The period ended in 1929, when the Lateran Treaty created the modern state of Vatican City.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prisoner_in_the_Vatican

The independent Vatican City-state, on the other hand, came into existence on 11 February 1929 by the Lateran Treaty between the Holy See and Italy, which spoke of it as a new creation

Following the fall of Rome, most countries continued to accredit diplomatic representatives to the Holy See, seeing it as an entity of public international law with which they desired such relations, while they withdrew their consuls, whose work had been connected instead with the temporal power of the papacy, which was now ended. However, no diplomatic relations existed between the Holy See and the Italian state.

According to Jasper Ridley,[5] at the 1867 Congress of Peace in Geneva, Giuseppe Garibaldi referred to "that pestilential institution which is called the Papacy" and proposed giving "the final blow to the monster". This was a reflection of the bitterness that had been generated by the struggle against Pope Pius IX in 1849 and 1860, and it was in sharp contrast to the letter that Garibaldi had written to the pope from Montevideo in 1847, before those events.

The stand-off was ended on 11 February 1929, when the Lateran Pacts created a new microstate, that of Vatican City, and opened the way for diplomatic relations between Italy and the Holy See. The Holy See in turn recognized the Kingdom of Italy, with Rome as its capital, thus ending the situation whereby the popes had felt constrained to remain within the Vatican. Subsequently, the popes resumed visiting their cathedral, the Archbasilica of Saint John Lateran, situated on the opposite side of the city of Rome, and to travel regularly to their summer residence at Castel Gandolfo,

Annexation of Venetia 1866Veneto or Venetia was part of the Roman Empire until the 5th century AD. Later, after a feudal period, it was part of the Republic of Venice until 1797.Venice ruled for centuries over one of the largest and richest maritime republics and trade empires in the world. After the Napoleonic Wars and the Congress of Vienna, the Republic was annexed by the Austrian Empire, until it was merged with the Kingdom of Italy in 1866, as a result of the Third Italian War of Independence.

House of Savoy, Italian Savoia, French Savoie, historic dynasty of Europe

ruling house of Italy from 1861 to 1946.

During the European Middle Ages the family acquired considerable territory in the western Alps where France, Italy, and Switzerland now converge.

In the 15th century, the house was raised to ducal status within the Holy Roman Empire, and in the 18th century it attained the royal title (first of the kingdom of Sicily, then of Sardinia).

Having contributed to the movement for Italian unification, the family became the ruling house of Italy in the mid-19th century and remained so until overthrown with the establishment of the Italian Republic in 1946.

The founder of the house of Savoy was Humbert I the Whitehanded (mid-11th century), who held the county of Savoy and other areas east of the Rhône River and south of Lake Geneva and who was probably of Burgundian origin.

His successors during the Middle Ages gradually expanded their territory. Amadeus V (reigned 1285–1323) introduced the Salic Law of Succession and the law of primogeniture to avoid any future partition of the family’s dominions between various

Music is the National Anthem of The Kingdom of Italy

Comments

Post a Comment